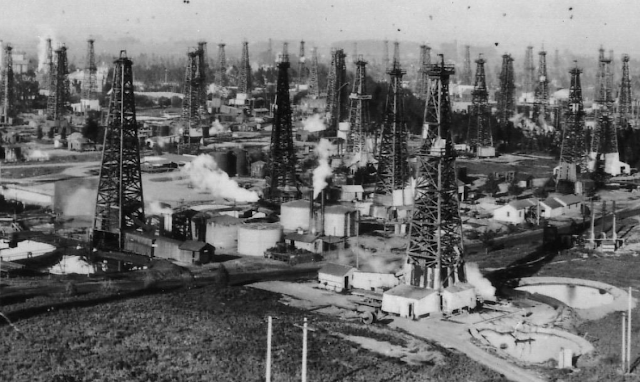

ABOVE: The oil field at Reservoir Hill in Huntington Beach circa 1920s, with a forest of oil derricks. Open soil sumps or ponds are visible, along with unpaved roads. The 1924-1925 recall attempt started as an objection to a "progressive agenda" that included paving roads. (City of Huntington Beach archives, snip of larger image, circa 1920s)

There have been nine documented city council recall attempts in Huntington Beach, since its incorporation in 1909.*

No level of government in the United States had adopted the recall of public officials until voters in the City of Los Angeles in January of 1903 opened the door. This was the time of the railroad barons. In Los Angeles, the first recall was fueled by a battle of the titans for railroad franchise lines of the Southern Pacific Railroad steam engines lines and Henry Huntington's Pacific Electric Railway's trolley lines.

The use of recalls as a tool for political activism grew exponentially in California and across the country. The first recall in Huntington Beach was in 1912. The second in 1925 was accused of Klan involvement and left deep political divisions in the community. The recall of 1935 involved a knockdown statewide battle for the rights and royalties of oil production on the beaches and tidelands.

1912 recall: Nine years after the 1903 Los Angeles recall effort, the first recall was attempted in Huntington Beach. The Huntington Beach Township Board of Trustees adopted Ordinance No. 102 in January 1912 for a special election in November asking whether or not Board of Trustees member W.D. Seely should be recalled.

Seely was chosen by his colleagues to be the Board's chairman in April 1912, in the midst of the recall campaign. "Mr. Seely received the unanimous vote of his fellow trustees," reported the Santa Ana Register on April 22, "...and assumed his new position amid the hearty applause of the large audience present."

LEFT: Ordinance No. 91 was adopted in 1912 during the recall campaign and moved forward a $70,000 bond issuance to rebuild the Huntington Beach wharf, destroyed by a Pacific storm. The wooden pier provided boat docking. W.D. Seely, the target of the recall, was chairman [mayor]. (Huntington Beach Board of Trustees minutes, May 13, 1912)

There is no description on the ballot regarding the reason for the recall, although there likely were accusations of personal gain. Seely, originally from Iowa, and his partner C.E. Lavering were successful realtors in a growing town having arrived at a time of investment opportunity circa 1906. The Board of Trustees was proposing improvements to attract more investment in Huntington Beach, such as the 1912 bond to rebuild the pier.

RIGHT: Walk to the narrow passageway on the left side of PERQS on Main Street and look up to see a tiny bronze name plaque on the Seely Lavering building, a legacy of the survivor of Huntington Beach's first recall attempt. By 1916, Seely was manager of the Tent City Co., had served as a justice of the peace, city recorder, mayor, and president of the Board of Trade. (Photo courtesy of Chris Jepsen, 2005)

The 1912 recall was unsuccessful. Out of a total of 444 votes, 285 voted against the recall and only 124 voted for a proposed replacement, D.O. Stewart. Stewart had served on the first Board of Trustees in 1909 and was a director of the Savings Bank of Huntington Beach.

LEFT: W.D. Seely served on the Board of Trustees from 1910 to 1914 and was mayor in 1912. Seely Park on Surfcrest Drive is named after him. (Photo, City of Huntington Beach)

Two days after the special election, Huntington Beach's first mayor Ed Manning announced his resignation to the Board of Trustees and asked Chairman Seely to schedule an election for his replacement. The resignations indicate a level of disgust at the local political climate. The Santa Ana Register reported, "It is now reported that Trustee French will also resign...It is evident that the faction war in this city has not decreased in bitterness, Trustee Manning's resignation demonstrating that the defeat of the recall of Seely has only enhanced the feeling of the two factions at war."

1924-1925 recall: This was probably the most contentious and complicated Huntington Beach recall of the 20th Century as relates to community identity. In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was attempting to infiltrate local government, law enforcement, religious and civic organizations. This also was in the midst of Prohibition, exploding growth from Huntington Beach's oil boom, and a wave of evangelical revivals in Orange County targeting the evils of gambling and alcohol. Two prominent evangelicals frequenting Orange County were close with the local Klan members, including receiving funding from the Klan.

All this coincided with local and county leaders maneuvering to block development of the Black-owned Pacific Beach Club between Huntington Beach and Newport Beach. The politics were confused. Some prominent local leaders opposed the Club while also opposing the Klan. Following two tumultuous political years, arsonists burned to the ground the almost-completed Pacific Beach Club in January 1926.

RIGHT: The Klan was a large part of the 1924 Labor Day parade and festivities in August 1924. Tom Lewis, a former Santa Ana newspaper man and "exalted cyclops" of Klan No. 2 was a scheduled speaker that day. By September 1924, the Orange County District Attorney A.P. Nelson was speaking out against the Klan and accusing them of soliciting memberships as a grift. In October, there were objections raised about the Klan participating in the November Armistice Day parade in Huntington Beach and they were essentially disinvited. (Santa Ana Register, August 29, 1924)

The recall purportedly started in 1924 as objections to the "progressive agenda" of town improvements, such as street paving and street lighting. Trustee and prominent oil man James Macklin outlined the proposed improvements for the Santa Ana Register in August 1924, including an "immense paving program...second to none in the state."

Macklin explained approximately $500,000 had already been spent and another $500,000 was needed to complete the program. The coast highway road was to be completed, as well as sections of the Pacific Electric Railway. An aviation field was planned for 23rd Street and Ocean Avenue (Pacific Coast Highway). They talked of aviation service between Huntington Beach and Catalina Island, aviation classes, and stunt flying every weekend as a sort of Pacific air show to attract visitors. There were plans to purchase beach front property for a grand pavilion that could host 5,000 people for dances and band concerts at the beach.

Huntington Beach was in an oil boom, couldn't keep up with demands for housing or services, and trustees wanted to strike while the iron was hot.

Brewing in the background in 1924, the Klan planned a rally in August at the Huntington Beach Labor Day parade with a family picnic. In Anaheim, the city council was trying to oust the Klan's influence and directing staff to remove Klan "KIGY" ["Klansman I Greet You] signs that had been painted on local streets.

LEFT: A small advertisement to hear Reverend L.E. Burger, affiliated with the Klan, at a meeting hall in Santa Ana. (Santa Ana Register, December 5, 1924)

Orange

County District Attorney A.P. Nelson spoke out against the Klan in 1924

and accused them of soliciting memberships as a grift along the lines of a pyramid scheme. The Klan sent out salesmen around the country. Memberships cost $10, of which the local Kleagle got $4, the King Kleagle got $1, and the remaining $5 went to the imperial treasure. Former Klan member Henry P. Fry confirmed the 1920s that, in addition to generating a white nationalist agenda, this edition of the Klan was a "money making scheme" (The Modern Ku Klux Klan; Small, Maynard & Company, 1922). The Imperial Wizard was raking in six figures, his organizers (Kleagles) got a piece of the action, and there was money to spread around and buy social and political influence.

"Barnum once said there was a 'sucker born every minute,' but when we look at the klan we are constrained to think that Barnum's estimate was extremely conservative," District Attorney Nelson said to a crowded Anaheim church. "How [anyone] with any degree of intelligence could be induced to pay $10 for the privilege of wearing a clown's suit and being admitted to the mummeries of such an organization as the klan is beyond the ken of the ordinary mind."

RIGHT: Orange County District Attorney A.P. Nelson "flayed" the Klan at a crowded church in Anaheim. He drew a connection between their desire to control personal conduct and morals with their growing involvement in political activities. ("Ku Klux Klan is flayed by Dis. Attorney," Santa Ana Register, September 29, 1924)

The Huntington Beach Board of Trustees set a bond election for $257,000, which included $100,00 for an extension to the municipal wharf, $12,000 for street cleaning and repair equipment, $25,000 for a sewer disposal plant, a purchase and improvements of oceanfront property for $75,000, another $20,000 for park improvements and town beautification, and $25,000 for a storm drain system.

The targeted trustees were accused of extravagance. The bond election failed. They would try again in 1925 to pass funding measures. Meanwhile, they could no longer ignore the creeping presence of the Klan.

LEFT: The Klan made a show of being "banned", aka cancelled, from a parade. Roy S. Horton, speaking for the Orange County Klan said they would "in the interests of peace and harmony" refrain from participation. He added a gentle threat, "we wish to state, however, that many Klansmen will be present..." as individuals. (Photo, Calisphere, 1924)

Three key things happened to further agitate the Klan's involvement in Huntington Beach: 1) the Klan was prevented from participating in the November 1924 Armistice Day parade after public objections from Anaheim and Fullerton, 2) Klan-friendly Reverend Elwood James Bulgin was refused the use of the City auditorium on January 27, 1925, by the Board of Trustees, 3) and the political and social climate of 1925 continued and likely encouraged arsonists who destroyed the Black-owned Pacific Beach Club on January 21, 1926.

Bulgin had been invited by Reverend Luther A. Arthur of Huntington Beach's First Baptist Church. (Read more about the First Baptist Church affiliation with the Klan: Prohibition and booze under the cornerstone)

RIGHT: Reverend Elwood J. Bulgin, the Klan-friendly evangelical preacher, invited to speak in Huntington Beach by the First Baptist Church and refused use of the City auditorium by the Board of Trustees. (Photo, Library of Congress, 1910)

Rev. Bulgin was a well-known evangelical preacher in the early 1900s, preaching on morality and sins of gambling, in the southland as well as a wider circuit throughout the Midwest and Pacific coast. He had become a darling of the Klan. A Klan newspaper (April 6, 1923, The Fiery Cross, Indianapolis, Indiana), describes 18 Klansmen marching down the aisle at a church in Indianapolis where Bulgin was preaching to present him with $600 dollars and a silk flag. Bulgin "in fervent language and a voice that shook with emotion" accepted the money in front of the congregation. The Fiery Cross referred to the Klan money as "six hundred bullets."

The Klan deployed similar theatrics to present Bulgin with money at his other appearances, including in Southern California. When the Board of Trustees barred him from using the City auditorium, the Santa Ana Register headlines shouted "situation in Anaheim tense" as the 1925 recall of four Klansmen from their city council moved forward. Also on the front page, the Santa Ana Register reported on civil cases filed (and won in 1908) against Bulgin in Orange and Riverside counties involving swindling and land fraud.

The first recall petition failed to gather enough signatures by December 1924. Recall proponents tried again in 1925. It was a messy affair with the pro-recall group hurling accusations and legal action against the City Clerk. Recall proponent William T. Newland filed a writ of mandamus against the City Clerk, which failed in Superior Court.

Chamber of Commerce president Samuel Bowen addressed rumors by recall proponents that Board of Trustees members gained financially from street paving contracts and that the chamber was colluding with the Trustees on an extravagant agenda.

Recall proponent Minnie Higgins complained she had not been paid $150 "which she was to have been paid for circulating a petition for the paving of Palm Avenue with Willite material." She accused the Board of Trustees of changing the specifications and the paving company then refused to pay her. In other words, a recall proponent thought city paving specifications shorted her out of money.

LEFT: Recall proponent Minnie Higgins at Alpha Beta Market, 218 Main Street, circa 1920s. (City of Huntington Beach archives)

"What you have read, and what you are basing your recall measure on are mere rumors and I am here to tell you that they are all lies," said city attorney L.W. Blodget at a community meeting in November 1924, who advised recall proponents the man they were defending had been convicted in superior court of fraud. "The charges were all deliberately made up and the man who made them up is a murderer of reputations. The man who repeats them is no better than the man who started them."

ABOVE: A view down Palm Avenue near 13th street, 1920. It was eventually paved. (City of Huntington Beach archives)

In early 1925, recall proponents circulated another petition. The signatures were certified as "sufficient" to the best of his knowledge by the beleaguered City Clerk. But, the official call for a special election was blocked by the Board of Trustees on advice of city attorney L.W. Blodget that the certification of signatures was "not positive enough to satisfy legal requirements." William T. Newland again filed a writ of mandamus in superior court to compel the Trustees to call a special election. It failed.

The 1924-1925 recall was unsuccessful. Like the first recall in 1912, months of political fighting took its toll. Trustee J. H. Macklin had had enough and submitted his resignation in June. As the recall faded in Huntington Beach, the recall virus was spreading and there were recall threats in Long Beach against councilmen who had refused to ban a bathing beauty parade in the interest of morality.

1935 recall: The 1935 recall threat centered around the battle to control the tidelands and oil drilling on the beach and shoreline. Three councilmen were targeted.

In 1929, the California legislature had passed a law to prohibit new oil production permits on the beaches and tidelands. Oil interests actively pursued loopholes. Huntington Beach wanted to lease land for oil drilling as a revenue stream.

RIGHT: Elson Conrad served on the Huntington Beach city council from 1928 to 1934 and was a supporter of the recall. He was president of Home State Bank when it opened on Main Street in 1923. Conrad Park on Aquarius Drive is named after him. (Photo, Santa Ana Register)

Then-mayor of Huntington Beach Elson Conrad and the City attorney L.W. Blodget signed on to the 1932 ballot's "no" argument on Proposition 2, arguing the State was missing out on millions in oil production income and should be able to develop the beaches and tidelands for oil revenue. They argued the "yes" proponents were creating "a smoke screen by yelling 'protect our beaches" while the "adjoining acreage is controlled by ONE company who had received approximately $6,000,000 from oil produced within 200 feet of said state-owned lands in the last four years."

Conrad and Blodget urged the financial benefit of the State leasing land from Huntington Beach and that the State could realize over $7 million in potential oil revenue, reducing the tax-payer burden.

The 1932 State ballot measure failed. The Huntington Beach city council meeting in closed session negotiated a new lease with Southwest Exploration Oil Company, hoping it had more political clout and could push through legislation in 1934 allocating oil rights to the City. [Land of Sunshine: An Environmental History of Metropolitan Los Angeles, William Deverell, Greg Hise; University of Pittsburgh; 2006]

LEFT: E. John Eastman is considered the "father" of directional drilling, which could allow for drilling on the mainland to reach oil pockets offshore. A summary of slant drilling history in Energy Global News notes two wells drilled in Huntington Beach in 1930 were the first recorded use of slant drilling. (Image, Energy Global News, March 15, 2020)

In May 1933, the Los Angeles Times reported the city council had approved a 20-year lease of land in the center of six city streets to Signal Oil and Gas Company, for which the City would reap 20-percent profits. The 24-foot strips were one to two blocks long down the center of 18th, 19th, 20th, 21st, 22nd, and 23rd streets.

By 1934, Mayor Conrad was publicly arguing with state finance director Rolland Vendegrift about the State tying up Huntington Beach leases. The State argued that the tidelands belonged to the State and filed suits against the City. "As a matter of fact," Conrad told the Associated Press, "I have been unable to understand the state's sudden concern about the slant drilling, when the Standard Oil Company for years has had wells sunk between the highway and the ocean. Standard now has seventeen wells that are 150 feet or more closer to the tidelands than the independent wells are."

RIGHT: Tom Talbert, former city councilman and mayor, a target of the 1935 recall attempt. Talbert Park on Magnolia Street is named after Tom Talbert. (Image, Santa Ana Register, September 25, 1928)

The recall was initiated after the city council endorsed a bill allowing drilling of the tidelands by means of whipstocked (slant drilled) wells from the mainland vs. from offshore islands. The proposed state legislation for offshore island drilling was defeated, slant drilling was approved.

Mayor Conrad had provided his resignation to the city council in order to run for Orange County District 2 supervisor in the November 1934 election. He lost the election to John Mitchell. When the 1935 recall initiated, Conrad had a little time on his hands and was a lead proponent.

The targets of the 1935 recall, Mayor Tom Talbert and councilmen John Marion and Anthony Tovatt, stated they wanted to preserve the beaches and tidelands for the public. The recall proponents argued that oil production on offshore islands were more protective of mainland that could be otherwise used. Council members were charged by recall proponents with "extravagance and squandering of public money, intimidation of employees, incompetence and lack of initiative."

The Huntington Beach chamber of commerce sided with the targeted council members and condemned the recall proponents. The Santa Ana Chamber of Commerce wired the governor urging him to veto Assembly Bill 1684 because it did not include all of Orange County's rights to oil royalties. "The County of Orange has certain participation rights to revenue accruing from leasing of oil bearing tidelands contiguous to its coastline," stated the chamber's wire.

RIGHT: Originally Circle Park, Farquhar Park is named after the Huntington Beach News publisher James Farquhar, who helped lobby the governor on the tidelands bill. (City of Huntington Beach archives, circa 1913)

In early June 1935, the California legislature passed the tidelands oil bill. Mayor Talbert and councilman Lee Chamness and Huntington Beach News publisher James Farquhar traveled to Sacramento to urge Governor Merriam to sign the bill. [Interesting note: pro-recall Elson Conrad was the former publisher of the Huntington Beach News.]

The first round of recall petitions were rejected for not meeting the required signature count. City Clerk Charles Furr announced on June 17, 1935, that the recall petitions for Tovatt and Marion received only 17 names each, the recall petition for Talbert only 22 names. A total of 380 names was required for each petition to quality.

Orange County Supervisor N.E. West (Laguna Beach) made a statement about influence of oil monopolies on the legislators in Sacramento. "During the recent debate in the assembly and senate...almost every legislator had large sheeves of telegrams," said West. "A great percentage of these were inspired by one of the great oil companies. In fact, one after another of these telegrams were verbatim and shown to come from the oil company employees and their relatives."

The 1935 recall attempt was unsuccessful. The targeted council members remained on the city council. The governor signed the bill. Oil producers still slant drill. Huntington Beach continues to receive oil lease royalties to present day.

The 4-decade pause: The 1925 and 1935 recall attempts were probably the most significant historically, although there were five additional notices of intent to recall in the last quarter of the 20th Century after a pause of almost 40 years. There are two recall attempts to-date in the 21st Century (one of which is ongoing as of this posting).

1974 recall: Notices of intent in 1974 from the Pet Owners' Coalition to recall council members Ted Bartlett, Alvin Coen, Henry Duke, Norma Gibbs, Jerry Matney, Donald Shipley, and City attorney Don Bonfa over the City's animal control ordinance was unsuccessful.

The City's election consultant informed that council members Coen, Bartlett and Gibbs were "immune from recall," as of the 1974 election they had not yet been in office six months.

RIGHT: Norma Gibbs was Huntington Beach's first woman city council member and mayor. She is remembered for her work creating the Central Library, challenging high-density development, and protecting the public beaches from encroachment. A 100+ year old eucalyptus grove "butterfly park" off Graham Street is named after Gibbs. (City of Huntington Beach archives)

Although the recall was unsuccessful, recall proponents were successful in getting the city council's attention. They wanted impounded cats to be held as long as dogs, making a license for a neutered animal a one-time matter, and the establishment of a citizen committee to review the police power of animal control officers. The City had contracted with a private firm instead of the Orange County Animal Shelter, leading some to believe there was a financial incentive to impound pets.

Columnist Bob Wells with Long Beach's Press-Telegram wrote, "Actually, I would rather wallow in Watergate than get involved in the pet controversy. I find Watergate much simpler than the problem of devising a series of regulations that will protect the rights of pet owners whilst protecting others from the pets."

Shipley Nature Center on Goldenwest Street is named after Donald Shipley. Norma Gibbs Park on Graham Street, also known as the "butterfly park," is named after Huntington Beach's first woman council member and mayor Norma Gibbs. Bartlett Park behind the Newland House Museum off Beach Boulevard is named after former mayor Ted Bartlett.

1978 recall: Notices of intent in December, 1978 to recall council members Ron Pattinson, John Thomas, Ron Shenkman, and city attorney Gail Hutton on the grounds of "incompetence, fiscal irresponsibility, failure to respond to citizen needs, conduct unbecoming elected officials and involvement in practices which appear to be deceitful to voters."

This recall was unsuccessful, due to not meeting the required 12,449 signatures for each of the petitions. Pattinson Park on Palm Avenue is named after former mayor and councilman Ron Pattinson.

1979 recall: New notices of intent in 1979 continued the 1978 recall effort to include council members Richard Siebert, Don McAllister, and Ruth Bailey. The recall centered around the council members "pro-development stance and failure to carry out the will of the people," per recall organizer Steve Schumacher.

This was a year after the city council approved a fast-tracked ordinance to permit hypnosis, for which the city clerk said it was "as if the council was brainwashed." ["Spells, magic, crystal gazing and hypnotism," October 29, 2021]

The Los Angeles Times noted the influence of Proposition 13, voters' growing distrust of government,personal criticisms of city staff during council meetings, and disputes among council members about how government should work. Almost 200 city employees left. "It was so bad, said one current employee, that you used to see secretaries off crying in corners." ["Power struggle turns Huntington Beach into a battleground," Los Angeles Times, December 26, 1978]

Police officers gave the city council a vote of "no confidence" in fall 1978, refusing to write traffic tickets and calling in sick with "blue flu."

The recall originally included councilman Ron Shenkman, a target of the 1978 recall. His name was removed after he resigned from the city council in December 1978.

This recall did not meet the required 12,449 signatures and was unsuccessful. Bailey Park on Morning Tide Drive is named after Ruth Bailey, who served as both a mayor and council member.

1996 recall: A notice of intent in 1996 by a member of the Huntington Beach Mothers' Club to recall Council Member Ralph Bauer, Victor Leipzig, Dave Sullivan, and Tom Harman was unsuccessful. Mayor Dave Sullivan came to Bauer's defense at a city council meeting to confirm his work for senior citizens and children. Bauer Park on Newland Street is named after Ralph Bauer.

2000-2001 recall: This recall kicked off the 21st Century like a crime show. In October 2000, a notice of intent by the Committee for Honest and Responsible Government to recall councilman Dave Garafalo ended up being, well...not needed due to criminal charges. Garofalo was being investigated by a trifecta of the Orange County District Attorney, the Grand Jury, and Fair Political Practices Commission.

Garofalo accused recall proponents of "environmental militarism" and accused the Los Angeles Times of "poisoned pen" coverage and being "swayed by underground press." In a letter to the Los Angeles Times in July 2000, he bemoaned "what price must I pay for bringing my belief system to public office?"

LEFT: Dave Garofalo at the time of the investigations into his conflicts of interest. (Los Angeles Times, July 2, 2000)

Garolfalo admitted he cast "about 300 votes on behalf of advertisers who gave him thousands of dollars to appear in local publications he owned" and from whom he derived revenue. ["Mayor: All an innocent mistake," Los Angeles Times, July 28, 2000] He owned the Local News and published the Huntington Beach Visitors' Guide. The Los Angeles Times reported Garofalo had voted 87 times since 1995 on matters affecting major advertisers in the Visitors' Guide. It was not a surprise for those who follow Huntington Beach politics when Congressman Dana Rohrabacher wrote a letter to the Los Angeles Times defending his friend Dave as an "honest, hardworking fellow."

The required signature count in 2000 was 20,000, with a possibility of a special election in April 2001. In the end, it was not needed. Garafalo resigned in December 2001 and pleaded guilty to criminal conflict of interest (one felony and 15 misdemeanor counts of political corruption), following an investigation by the Orange County District Attorney.

Judge Ronald Kreber sentenced Garofalo to three years unsupervised probation and ordered him to pay a fine of $1,000, plus 200 hours of community service and a penalty of $47,000 to the Fair Political Practices Commission for failing to accurately report sources of income and gifts. He remains barred from holding public office.

2021-2022 recall: As of this posting, the attempt initiated in August 2021 to recall five Huntington Beach city council members is not yet over. The first petition naming Mayor Barbara Delgleize and Councilwoman Natalie Moser was unsuccessful in gathering the minimum 13,000+ signatures by February 5, 2022.

Recall organizers missed legal paperwork details and deadlines in 2021, requiring they try again to meet requirements for recall petitions against three additional council members. Just like the 1925 recall attempt, there have been accusations made against the City Clerk. The second batch of recall petitions regarding council members Dan Kalmick, Kim Carr and Mayor Pro Tem Mike Posey are pending and due February 23. [This will be updated.]

*Did we miss a Huntington Beach recall? It's hard to keep up. Send us an email and we'll add it.

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Huntington Beach blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.