The

annual Huntington Beach Cherry Blossom Festival is Sunday, March 18, 10:30

a.m. to 5:30 p.m., behind the Central Library at 7111 Talbert Avenue and

Goldenwest Street. The event includes live entertainment and music, Japanese cuisine, cultural exhibits and performances. Early arrival is recommended for free parking in the Central Library

parking lot and nearby lots. This event celebrates Huntington Beach's multi-decade Sister City relationship with Anjo, Japan, and supports the student ambassador program. (Photo, M. Urashima, 2015) © All rights reserved.

It took two attempts to bring the first gift of cherry trees to the United States from Japan. The first shipment of 2,000 trees in 1910 were not healthy enough to plant. The second shipment of 3,000 trees from Mayor Yukio Ozaki of Tokyo to the city of Washington, D.C.

in 1912 were a success! It is the recognition of that gift that

sparked the National Cherry Blossom Festival along the Tidal Basin.

LEFT: In Japan, the face of the moon is a rabbit mochi-tsuki: rabbits pounding cooked rice in a mortar to make mochi, the confection enjoyed at special holidays and festivals. Dango, or mochi, is often shaped like a rabbit at the time of the fall moon festival and like cherry blossoms during hanami, or "flower viewing" season. (Image, National Diet Library, Japan)

It was an idea with roots in the late 19th century, with the writer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore. Scidmore was an aberration. She wrote the first travel book for Alaska and was the first woman to write for National Geographic. Scidmore wrote about her experiences traveling in Asia and lived in Japan. She would write about Asia for decades, introducing American readers to the Japanese moon festival, and explaining that, while Americans saw a "man in the moon", in Japan the image on the moon's face was seen as "rabbits making mochi."

RIGHT: Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, described as a writer of "sparkling travel sketches" by the Minneapolis Journal, March 16, 1901. She was the first to advocate for the planting of cherry trees in Washington, D.C. Washington Post writer Michael Ruane wrote in 2012 about Scidmore's appearance at a Capitol society bal in the winter of 1894, "she wore a gown of green under a black silk robe embroidered with gold and silver Japanese characters. And when the young woman walked into the Dupont Circle mansion that night, she turned every head...She was 37, an author, journalist, traveler and collector of the lore and artifacts of far-off lands." (Photo, Wisconsin Historical Society)

While she wrote about cultural traditions and flower festivals--such as the festival in Japan for asagao, or the morning glory flower--Scidmore also was acknowledged as an insightful observer of the social and political environment in Asia, publishing works like, Java: The Garden of the East in 1987, and China: The Long Lived Empire in 1900.

The U.S. National Park Service credits Scidmore as the first to advocae for cherry blossom trees in 1885.

LEFT: Cherry trees in bloom in Aakasaka, an area of Tokyo, in the 1890s. (Photograph, The New York Public Library. ID 109995. Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs)

"Upon returning to Washington from her first visit to Japan," reports the National Park Service, Scidmore "approached the U.S. Army Superintendent of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds, with the proposal that cherry trees be planted one day along the reclaimed Potomac waterfront. Her request fell on deaf ears. Over the next twenty-four years, Mrs. Scidmore approached every new superintendent, but her idea met with no success."

In 1909, Scidmore made the request of the wife of President William Howard Taft, First Lady Hellon Herron Taft, suggesting she would fund raise to buy the cherry trees and donate them to the Capitol. The National Park Service explains that the First Lady had lived in Japan and was familiar with the sight of the cherry trees in bloom.

RIGHT: Tanabata Festival, or Star Festival, kazari on display in Huntington Beach Central Park during the 2017 Cherry Blossom Festival. (Photo, M. Urashima, 2015) © All rights reserved.

Hellen Herrron Taft responded to Scidmore in two days, writing, "Thank

you very much for your suggestion about the cherry trees. I have taken

the matter up and am promised the trees, but I thought perhaps it would

be best to make an avenue of them, extending down to the turn in the

road, as the other part is still too rough to do any planting. Of course, they would not reflect in the water, but the effect would be very lovely of the long avenue. Let me know what you think about this."

The Washington Post continues the history, explaining that the day after Scidmore received the letter from the First Lady, "she told two Japanese acquaintances who were in Washington on business: Jokichi Takamine, the New York chemist, and Kikichi Mizumo, Japan's consul general in New York. The two men immediately suggested a donation of 2,000 trees from Japan, specifically from its capitol, Tokyo, as a gesture of friendship" and asked Scidmore to find out if the First Lady would find the gift acceptable. She did.

LEFT: A program for the 1949 Cherry Blossom Festival in Washington, D.C.

With First Lady Taft's support, things moved quickly. Although the first batch of cherry trees could not be planted, the second group arrived from Japan just in time for Valentine's Day, February 14, 1912. Over three thousand trees were shipped from Yokohama to Seattle, then in insulated freight cars went on to Washington, D.C. And, on March 27, 1912, the First Lady and the Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese Ambassador, planted two Yoshino cherry trees on the northern bank of the Tidal Basin.

ABOVE: Cherry blossom trees burst with color in Huntington Beach Central Park. Most of the trees are gifts from Sister City Anjo, Japan. Each year, a new tree is planted with a delegation from Anjo and with the Consulate General of Japan, near the Secret Garden. (Photo, M. Urashima, March 2017) © All rights reserved.

That year, the Washington Star reported a "Washington woman who has been decorated is Miss Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, whose home is at 1837 M Street northwest, and who in 1908 was given the cross of the Order of the Eastern Rising Sun by the Emperor of Japan in recognition of her writings in Japan." (Editor's note: Scidmore's home remains standing at the address reported in 1912, a stately, restored Victorian, now living a new life as a restaurant.)

LEFT: The United States has long been fascinated by the traditi9on of hanami, or "flower viewing" of the sakura (cherry blossoms) in Japan. (It's Cherry Blossom Time In Japan, San Francisco Call, April 21, 1907)

The National Cherry Blossom Festival reports that several years later in 1915, the United States reciprocated with a gift of flowering dogwood trees to the people of Japan. In 2012--a century after the planting of Japan's gift of cherry blossom trees in Washington D.C.--the United States sent 3,000 flowering dogwood trees to Japan as an anniversary gift. The dogwood trees were planted in the Tohoku region of northern Japan and in Yoyhogi Park of Tokyo.

To preserve the original genetic lineage of the first cherry trees, the National Park Service reports that "approximately 120 propagates from the surviving 1912 trees around the

Tidal Basin were collected by NPS horticulturists and sent back to Japan

(in 2011) to the Japan Cherry Blossom Association...Through this cycle of giving, the cherry trees continue to fulfill their

role as a symbol and as an agent of friendship."

RIGHT: Look for the large stone among the cherry blossom trees in Central Park, commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Sister City friendship with Anjo, Japan, dedicated in 2002. The stone reads, "Each spring in Japan, cherry blossoms are enjoyed as a symbol of renewed live and vitality. In this spirit, Anjo, Japan, has given fifty cherry trees to the City of Huntington Beach to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Sister City relationship between Anjo and Huntington Beach." (Photo, M. Urashima, March 2017) © All rights reserved.

This year in Huntington Beach, we will again plant new cherry trees in Central Park--and celebrate an international relationship that began with the first Japanese pioneers in Orange County in 1900 and with a Sister City bond beginning 36 years ago. Come join us for good food, music, cultural performances, good friends, and the simple art of viewing flowers.

All rights reserved.

No part of the Historic Huntington Beach blog may be reproduced or duplicated

without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams

Urashima.

Monday, February 19, 2018

Monday, January 8, 2018

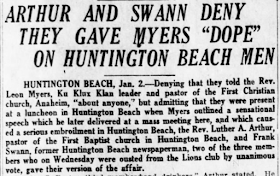

Prohibition and booze under the cornerstone

If you have seen the initials "J.E.B." marked on a curb in the historic downtown, then you have seen the work of James E. Brunton. He was a contractor for the city in the early 1900s as the Huntington Beach Township grew, gradually adding sidewalks and paving streets. Brunton's name shows up regularly on the board of trustees minutes (the early city council) for approval of payment for his work. He also worked as a private contractor on major projects, such as the construction of the Holly Sugar Company factory.

ABOVE: Not much of the original sidewalk and curbing is left in the original Huntington Beach Township area. The initials J.E.B. mark the work of James E. Brunton, who was a longtime resident, local contractor, and civic leader. He served on the election board determining whether or not a bond issue to rebuild the pier would go on the ballot in 1912. (Photograph, M. Urashima, 2014) © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Brunton is a figure in a rumor published 92 years ago on this date by the Santa Ana Register, during the thick of the Prohibition years in the United States. The Eighteenth Amendment mandating national Prohibition law began on January 16, 1920. The myth of the whiskey-under-the-cornerstone grew legs on January 8, 1925.

ABOVE: Orange County Sheriffs dumping illegal booze in Santa Ana in 1932, with supervision from some determined looking ladies. (Photograph, Courtesy of Orange County Archives, March 31, 1932)

The Huntington Beach board of trustees (city council) did not enact Ordinance #223 enforcing Prohibition until August, 1921, over a year and a half after the national law went into effect. The discovery of oil in 1920 may have slowed down the local enforcement, but by 1921---with hundreds of oil workers descending on the town---things were getting a bit rowdy. By late 1921, Huntington Beach was technically dry (doctors could still prescribe whiskey for "medicinal purposes").

To put it mildly, banning anything has never been too popular in Huntington Beach, from fireworks to plastic bags. Although the city has a history of imposing restrictions on alcohol--with the first ordinance regarding "public drunkedness" enacted in 1911 (#72), and many more in the years that followed--there doesn't appear to have been a fondness for Prohibition.

Private alcohol stockpiling was rampant prior to Prohibition taking effect in January 1920. So was bootlegging alcohol or moonshine after the law was enacted. By 1925 and five years in, the American public, journalists, and humorists, were fairly certain Prohibition was not working. People found creative ways around the law and alcohol was still available, leading humorist Will Rogers to remark, "Prohibition is better than no liquor at all."

LEFT: The birth of a myth. The Santa Ana Register published an unverified "story" that cement contractor James E. Brunton "put a full bottle of whisky under the cornerstone of the First Baptist church of this city" when it was constructed in 1913. (Santa Ana Register, January 8, 1925)

The myth circulated by the Santa Ana Register in 1925 was that Brunton had placed a full bottle of whiskey under the cornerstone of the First Baptist Church when he laid the foundation in 1913, seven years before Prohibition. With tongue-firmly-in-cheek, the Santa Ana Register upped their game by adding that there also was a petition asking "that the Pacific ocean be dried up". It was the "wets" versus the "drys".

There is a more serious back story to the Santa Ana Register poking fun with their whiskey-under-the-cornerstone story.

The Santa Ana Register was hinting at a heated public feud between the pastor of the First Baptist Church, Rev. Luther A. Arthur, and the Huntington Beach Lions Club of which he had been a member. Rev. Arthur publicly stated he had found empty bottles of "Jamaica Ginger...smelling strongly of booze in vacant lots all over the town" and that he had also found a bottle in the back room of his church.

RIGHT: Jamaica Ginger, a remedy for stomach ailments and cramps, had an alcohol content as high as 90 percent (Source: "Alcohol as Medicine and Poison", The Mob Museum, themobmuseum.org)

"When I found a bottle in the back room of this church, you bet I got hot," the Santa Ana Register reported the pastor's remarks on January 5, 1925. Prior to this, Rev. Arthur had spoken to the Lions Club and, as he put it, had worked "against two of its members politically, because I believe them to be mixed up with booze."

In a small meeting, the Lions Club quietly removed him from their membership. Then, Rev. Arthur made it loud.

LEFT: Rev. Luther A. Arthur delivered a fiery sermon against alcohol and the local Lions Club on the evening of Sunday, January 4, 1925. Angered that he was booted out of the Lions Club, his sermon revealed that he had brought a leader of the Ku Klux Klan to Huntington Beach. While Rev. Arthur denied the Klan's involvement, it was well known that Rev. Myers was the Exalted Cyclops of the Anaheim klavern. Myers had embarked on a series of public meetings at which he made unsubstantiated accusations against various community leaders. Three years later in 1928, Huntington Beach mayor Samuel Bowen would run successfully for office on an anti-Klan slate. ("Sin is centered in booze, asserts Huntington Beach parson in Sunday sermon", Santa Ana Register, January 5, 1925)

In his January 4, 1925, sermon, Rev. Arthur asserted that Huntington Beach was the veritable capital of alcohol violations in Orange County. To support his fight against alcohol---prior to being booted out of the Lions Club---Rev. Arthur had brought to town the Reverend Leon Myers, pastor of the First Christian Church of Anaheim.

Myers had another role: he was the Exalted Cyclops of the Orange County klavern of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had taken an active position supporting Prohibition and Myers had been enlisting pastors and bible clubs to spread their message.

RIGHT: The Santa Ana Register detailed the visit by Rev. Leon Myers, Exalted Cyclops of the Anaheim Ku Klux Klan and noted that ousted Huntington Beach newspaperman Frank Swann was departing to work for the San Jacinto Register, "owned by Chester M. Kline, state senator and prominent klansman." The Santa Ana Register pointedly ran this article next to a feature, "School work to get Lions Club help", touting the Lions work on the betterment of Huntington Beach elementary schools. ("Ousted Lions glad to get out of club", Santa Ana Register, January 2, 1925)

In November 1924, raids on suspected bootleggers had been organized by Dr. W.S. Montgomery with the California Anti-Saloon League and William Starbuck, a colleague of Rev. Myers. While not reported, it is inferred there may have been members of the Lions Club caught up in the raid and that Myers had instigated the raid. Hence, the action taken to remove Rev. Arthur from their membership.

The Lions Club--along with the Kiwanis, Rotary, Elks and the Anaheim Masonic Lodge--already had taken public positions against the Klan in 1924.

In a rather pointed editorial decision, the Santa Ana Register published the story on Rev. Arthur's sermon immediately adjacent to an article reporting "Prohibition made little headway in 1924 if arrests for drunkenness may be taken as an index". It appears both the Santa Ana Register and the community had enough of this Prohibition nonsense, temperance vigilantes, and, enough of the Klan. It was the beginning of a push against the Klan, which had taken root in Anaheim and was attempting to get a toehold in other cities.

LEFT: The Orange County Grand Jury found in January 1925 that the "charges hurled by Rev. Leon Myers and William Starbuck at various public mass meetings were thus discounted to the vanishing point...merely hearsay and without corroboration." Starbuck was a rancher from Fullerton and its first druggist. ("Charges by leaders of Klan found groundless", Santa Ana Register, January 14, 1925)

Less than a week after the Santa Ana Register ran its whiskey-under-the-cornerstone story, the Orange County Grand Jury published their findings that the charges made by Klan leaders at public meetings were groundless and had no merit. The Santa Ana Register published the Grand Jury report to clear the names of those maligned.

By February 1925, several Orange County newspapers refused to report on any Klan-related subjects, denying them coverage. Anaheim passed a series of laws to remove the Klan's influence and organizing ability, including prohibiting the distribution of handbills. But, it would take the rest of the 1920s and 1930s to effectively send the Klan back underground.

There is no whiskey under the cornerstone of the First Baptist Church building in Huntington Beach. No need to dig that up.

Editor's note: The 18th Amendment was repealed with the ratification of the 21st Amendment on December 5, 1933.

© All rights reserved. No part of the Historic Huntington Beach blog may be reproduced or duplicated without prior written permission from the author and publisher, M. Adams Urashima.